“Who’s fighting and what for?”

Ringing out through a packed racetrack-turned-music festival, these words fell from Mick Jagger’s lips as he attempted to assess a situation of political unrest from a stage created haphazardly in an attempt to make another one of the great festivals of the 1960s. This festival would live in infamy, not because of its headliners, nor its location, but for the death of the sixties in the eyes of its once shining star, caught on camera for the world to see.

It’s hard to deny the help The Rolling Stones were to push the counterculture to the mainstream during the early to mid 1960s. They never shied away from being snarky, they didn’t care much about a good public image, and they were a huge and vocal force for women and civil rights during a time when most stayed quiet on the matter. It was them that pushed mainstream music in a slightly heavier direction, along with normalizing ideas of self expression through clothes and lyrics. By 1969, the culture had more or less caught up with the blueprint they had first laid out, becoming mirrors of the image of the Stones they had last seen in public. During that year, the Stones would move even further within these confines, no more biting their tongues to give a well suited answer nor dressing to please the status quo at all, even their indulgences of sex and drugs had become less taboo via the mainstream. Mick Jagger had emerged as the bands ambassador, this had come after years of becoming hell bent on proving to the world that he was never like his contemporaries, that he was not to be thought of as a brain-dead prop whose strings were held by a record label to make him palatable to enough to be mass sold to teenyboppers who wanted to tear him apart. He was sauve, proving to an older generation that rock and roll was here to stay while showcasing to young people that someone heard them and was willing to speak as their voice. He was a study in not judging a book by its cover when that was becoming a fixture, after all it wasn’t everyday that someone so of their time could also prove to have intelligence that extended so far beyond their years. He was full to the brim with wit, too fast to ever have a fair debate with - he had little to no respect, but gained a following of people quietly allured by his demeanor, people who simply could not deny his role as the speaker for a cultural zeitgeist. Announcing the tour, Jagger was asked how he was

philosophically and financially, to which he quickly retorted: “Financially - dissatisfied. Sexually - satisfied. Philosophically - trying.” He was emerging as someone who people aimed to watch fail, how could someone root for someone so smug? You couldn’t, but when it was Mick Jagger in 1969? Well, there was little he couldn’t escape from with just his name and likeness.

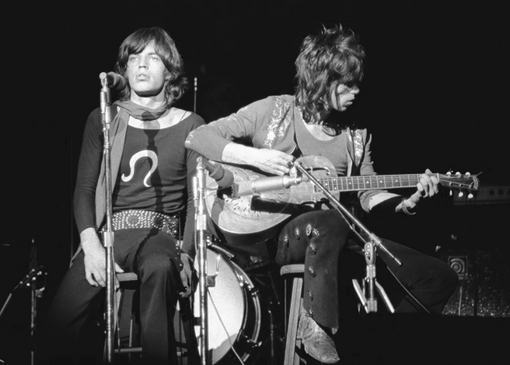

To be fair, to be any member of The Rolling Stones in 1969 was something that could get you away with highway robbery. How could anyone deny Jagger was emerging as the absolute coolest image of the year when suddenly you placed him on a stool next to Keith Richards, who easily become an equal to a man with none in mere seconds. He could charm anyone by aiming to not charm, someone who cared so little he said he viewed any publicity as good publicity and was actively the hardest person to speak to was suddenly a character

more captivating than ever before. The new guitarist. Mick Taylor, was garnering a whisper amongst everyone questioning how a 20 year old could replace Brian Jones. He proved himself quickly and quietly - becoming beloved amongst rock music fans for his live and studio chops that made him a rival to any and all of his extended peers. Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman were proving to be one of the tightest live rhythm sections of their day, while bands like Zeppelin or The Who’s rhythm was become extraordinary and a full performance in and of itself, Watts and Wyman locked into their groove in such a subtle way it was spectacle in and of itself. There was nothing the band could do wrong, on a winning streak after proving they could release phenomenal studio albums and singles, there was nothing left to do but tour and prove to the public just what got them to their juncture. The tour was a big deal even before it found itself as a fixture of history, that being it was the Stones first tour of the States since 1967, their first with Taylor, and first with the newly realized version of the Stones, the version that would go on to define rock and roll for the foreseeable future. The tour was marked by the band being what they always had been: agents of the counterculture. While artists like The Doors and Jimi Hendrix had made live performances spectacle, captivating audiences with presences that filled the void left by the Stones, the band captured back exactly what made them so important in the first place. Jagger would snidely flirt innuendos at the audience, toss rose petals over the first few rows as he waltzed on by, quickly escaping any crazed fans who ran onstage while barely missing a beat. The tour was slated to end with a massive free show, making up for the band having been unable to attend any of the major performances of the decade due to a mirage of reasons: court hearings, movies, pregnancies, you name it. The idea to end the monumental year the band and world at large experienced in 1969 with a festival show was a given. The original ideas was for where the band were to perform were shot down for mirages of reasons, until the general idea of a free concert in the San Francisco area was decided. There was an idea to do a free show as the Grateful Dead had in one of the famous parks around San Francisco, but the idea fell through there when there was a ban on live music to be performed on stages around the parks. The idea was eventually settled - a week before the show - that it should be held on a raceway in the middle of California. Before the show was even set in stone there was a list of annoyances that acted as an omen of what to come.

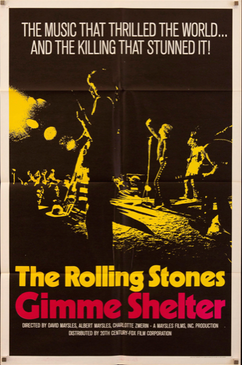

Before the festival though, it’s important to discuss the tour that it was marking the end of. This tour is what gave the exact reference point of the band for years to come, it cast Mick Jagger as exactly who he’s come to be known as, the image of a skinny bloke in women’s clothes that galavants across stage without a care of others thoughts was first realized here. The tour of 1969 was regarded highly the second it set its caravan on the road. The openers were heavy hitters like no other, headliners in their own right, from Tina Turner, to Chuck Berry, even B.B. King was opening for the Stones on some dates. The band themselves would debut some of their classics for the first time, tour debuts of Street Fighting Man, Sympathy for the Devil, Let it Bleed. They were a tour de force before that meant much of anything, so good that their ticket prices were causing backlash: they were charging $8.50 a ticket. The Stones, in a few short months, were eclipsing all their competition, their ability to make people care in a year where Woodstock brought together every huge artist of their time and where The Beatles would release arguably their best album, Abbey Road. The year established the Stones as an institution unable to be messed with, they were capturing culture when by all accounts they were not the “it-thing”. Everyone may have been at their peak, but no one was The Rolling Stones. What was fascinating about the affair was there was already a writer, Stanley Booth, and a film crew following the band through the states in an attempt to canonize the experience as it played out. The pieces, Booth’s The True Adventures of The Rolling Stones and the documentary Gimme Shelter, both preserve the tour that lead up to Altamont in perfect sincerity, never shying away from the less glamorous parts of rock stardom, acting as absolute essential pieces in the pantheon of music history.

Booth's book, Jagger and Richards on stage in 1969 by Michael Ochs, poster for Gimme Shelter

To touch on the festival again, it should never be ignored that Altamont came from the three biggest pitfalls of Mick Jagger at the time: Ego, money, and hope. The idea for the show originated as “Woodstock west” capitalizing on the largely successful trend of music festivals and giving them something no other had yet to see: the Stones. The band’s inclusion at Altamont, especially as headliners, gave it the draw, especially as it was coming off a stint away from America that had lasted almost three years. In those three years, the band had grown even more popular than before and were the natural big ticket they always are. The finance aspect came from the billing as free, it was free, but it can be assumed there would be a cut of pay for the artists performing. The last bit, hope, is something that has become vacant from Jagger since this excursion. There was an air about the late 1960s that played into a false ideal that people won’t ruin good things. There was unrest that was unlike anything that had ever been seen, while a war raged on, a group was able to come together not for the reason of not war but of love. It was idealized, but it was real for a short time. Due to the political unrest of the time there was a very valid and specific reasoning for not using the police as security. The Grateful Dead, the “prime” organizers of the event, had given Jagger the idea of using the Hell’s Angels as security as when they had done it in the past everything had worked out fine. This advice, if you’d call it that, was taken, the Angels were used as security. It’s easy to call upon the writing on the wall here, how hiring a biker gang to do security for one of the largest festivals of the decade was always going to go bad, but cultural context is a necessity to understand how that decision was ever made. The Grateful Dead were hugely popular in the San Francisco area where the event was taking place, and they were no strangers to free concerts or drugged out audiences. If things had gone fine up until now with using the unqualified security, why would that suddenly become an issue on a random December day? There was also the fact that the group that was expected and marketed towards showing up was infamous for their peaceful and non-violent demonstrations in large gatherings. Between what had happened at other festivals of the time and the large anti-war protests organized by these same people, why would there be a thought something would turn deadly? It’s easy to see how these ideas are seen as quite naive with the context, but Altamont was the first inkling of that context on a center stage. If you were Mick Jagger in 1969, being upheld as a divine figure of live performance, you probably wouldn't think about where things would go wrong either. If you never had to before, there was certainly no reason to start as you grace the peaks of stardom.

During the 1960s, there was an unforeseen amount of violence and civil unrest that was taking place constantly. From the moment John F. Kennedy was shot nothing was the same. It was the opening of the floodgates in many respects, JFK was a figurehead for the youth and was blown away, suddenly pop culture filled in the gaps he left, acting as the voice of the youth in a way that it never had before. Instead of being something that was simply marketed towards youth, it became the voice of the youth. Protest was flooding the airwaves, the gap between artist and fan was minuscule, everyone was on the same page. It was viewed as “dangerous” by the governments, how the youth were suddenly not the outspoken few but the silent majority. It’s how a figure like Mick Jagger could get on television and debate with people, or how Bob Dylan would be a God amongst men, how John Lennon would be kicked out of the US for the effect he may have on the public. As progressive figures began to be assassinated at an alarming rate was correlating with 16 year olds being sent to fight in a losing war. The media being created by their peers was no longer for entertainment, but to incentivize them to fight against the powers that be. How just months after the progressive Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated outside of a speech addressing supporters, a song could chart with a lyric insinuating the evils of humanity for killing him and his brother in cold blood. It may have scared the older generation, but for the younger generation it was a wake-up call that this wasn’t normal nor something to take lightly. It showcased what Stanley Booth would later write of, saying “In the sixties we believed in a myth - that music had the power to change peoples lives. Today we believe in a myth - that music is just entertainment.” After the turbulent 1968, ‘69 was a year of organization against what had been happening. Things didn’t calm down, but they became more controlled in how they were discussed and understood. After Woodstock, John Lennon would remark that it was the biggest gathering of people for something other than war. There was a unity that was emerging between everybody that seemed hard to deny it’s overly positive impact that was beginning to form around these large gatherings of like-minded, peaceful people. In the face of danger and uncertainty, there was beauty almost overflowing from each of these events and the people who helped make them happen. It wasn’t that there weren’t issues, it was just a case of good outweighing bad, many times over. That’s rare. There was no inkling that Altamont could go wrong because it would stick out like a sore thumb if it was to…

“Woodstock is the biggest mass of people ever gathered together for anything other than war.” - John Lennon

Stanley Booth was with the Stones each step of the way, making his statements about the music all the more powerful. The Stones, while dappling in protest, were not as political as their counterparts, but still figures of a revolution their generation was begging to begin. Booth comes across as an outsider in this world, almost unaware that a group of 20 year olds he knew as the same as everyone else held so much power over the youth. He called out hypocrisy amongst them and their team, how Mick Jagger could float across stage singing about killing the king as his managers beat on teenagers doing nothing wrong. How no matter how progressive the bands messaging was the world wasn’t catching up. What underlines this even further was his walkback on these ideas once on the ground at Altamont. It was there he painted a portrait of Jagger as an agent of change that wasn’t as false as he once assumed. There was an understanding from him that Jagger was forced to exist in a certain context that prevented what he was now witnessing from happening elsewhere. While it seemed once that Jagger could be aloof towards (or worse, complicit) with what those around him were choosing to do in the name of his band and likeness, it became obvious Jagger was just as stuck as any other person in that world. He wasn’t, at that time, lying when he said his name was disturbance and that he wished to rail at all the king's servants, he was simply stuck between losing his spot as a voice for the people or letting people do wrong so he could reach further than an arena. Booth realized this in the

moments before Jagger went onstage at Altamont, knowing full well that Jagger would’ve been right if he chose to leave to save his own skin after the horrors that had already transpired throughout the day. It was once Mick arrived on property that he was punched in the face for no reason, falling to the ground less than two minutes after arriving on property of the free concert he was hosting: if he left there he would’ve been in the right. If he left once he found out about all the issues being had with Angels and other artists, he would’ve been in the right. It was when Jagger was offered a police escort out of the Altamont after his set in which he denied that Booth realized just how much Jagger had been doing up to this point. How everytime he could’ve taken the easy way out that would’ve saved his own ass he didn’t budge, sticking it out with all the people he hadn’t been able to help any other time, how he never lied when proclaiming there was no place for a street fighting man. Booth wrote of Jagger in that moment:

"For some reason, as he stood surrounded by Hell's Angels in the world's end of freakdom denying the only safe way out, I was proud to know Mick Jagger." - Stanley Booth, 1969

There’s something about the image of Mick Jagger, ever level headed, standing before a group of people no older than himself calling for peace despite his fear of doing so. He was no more than twenty-six at the time of the show, and suddenly was called upon to act as the voice of reason in a situation so far unfixable he would’ve caused a riot no matter what choice he chose. The simple repetition of his plea, Who’s fighting and what for? rung much further than where his voice could actually carry. After a decade of unrest, there was finally a breath of calm with these large shows, yet the undercurrent still swept these moments away too. The calm before the storm. There’s a certain look Jagger gives as he sees a scuffle break out, a mix of fear and confusion, that has come to be known as the moment the hippie generation died. Jagger didn’t know that fight had turned deadly, but his face shows that the worse was already assumed. It’s a moment that could never be manufactured, something that breaks up the otherworldly phenomenon that had been following the band that year, something so horrible it could be nothing but human.

There’s so much that goes into the allure of this fraction of time, the one night in 1969 that the whole world genuinely seemed to shift into a spot it has yet to leave. The music serves as a backdrop to some of the scariest moments experienced in these young people's lives, its status as a form of escapism that got ripped away in a matter of seconds. The death of the peace movement, of a generation - the ideology held by a group of people who never wanted to become the people they fought against disintegrating into the night like the last embers of a once raging fire. How do you even begin to process the likes of Jagger and Watts watching over the footage with an emotionless gaze? Any joy they’d once derived from the performances or music meshing with pain and suffering, right before their eyes as they replay the moments they’ll forever hold as their fault. How the event created a shift in not only Jagger, but lit a fire beneath every artist that showed they were never allowed to just make art but be responsible for each thing that could happen under their inexperienced gaze. There’s a certain hopelessness and anger that can be felt in Richards’ voice as he calls for peace, threatening to go out there and defend the people that everyone seemed to turn a blind eye towards. How did it become he who had to stand before a crowd and yell for peace? When did it become his job to remind people of empathy and respect to their fellow humans? How did it get to a point where a person so unqualified had to do what everyone else was afraid to do? How could things have gotten to a point where a non-violent performer stands upon the stage, going from the silent observer to the person forced to the front to reckon with the spill-over of the violent and political climates of the world? How could that come to be? It’s dystopian. When did it become anyone’s job to break up fights caused by hate that is so easily avoided? How did the world get to a point where it was so divided there wasn’t a day that could go by without a deadly moment to forever stain the lives of those involved?

The death of Mereith Hunter.

The thing about Altamont was that it told much more about the future than the present. At the time it was a complete shock that something so depraved could happen at a show,

something so devoted to all the peace, love, and happiness that was being spewed by the attendees. It showcased how the unrest and turmoil from the rest of the world was apt to seep into things that had no link to those ideas. How people ignore the problems they have part in causing, how nowhere is safe from people who are violent and mean spirited, that the youth cannot cause a revolution because the powers that be always have a way to shift off their share of blame. It’s how Mick Jagger became public enemy number one for the violence caused in reaction to the wars raging on and the political ideologies of a government and country he didn’t even hail from. The blowback from Altamont is still felt today, it's ingrained in American culture but not for reasons it should be. It should have been a portrait of its time, an example of what could happen under these conditions, not the blueprint for the next fifty-five years of American culture. The film, released by Jagger in an attempt to open a civil dialog about the incident and not hide its existence away in a vault to save his own image, acts as more than a time capsule or concert film. It’s the living preservation of where the world went wrong and how far some people will go to ignore it. How people will still spew the narrative Jagger chose to release the doc to compete with the Woodstock film when Stanley Booth wrote that on the very night of Altamont, Jagger was already thinking about the film’s release to showcase the full story and how it happened. Jagger’s exact words are transcribed as the following: “I don’t want to conceal anything.”

An interview with Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone magazine, was released in late 2023 and became viral for his out of touch look at the world. In that interview, journalist David Marchese asked him a simple question: do you have any critiques of your generation? After some thought, some different perspectives added, Wenner said: “We were very lucky. We’ve lived really privileged lives. Now we get to rest. At the same time, we can look at our kids and the world we leave behind as being motivated and as inspired to do the same thing.” The admission of being privileged is the important part here. This was the same man that expressed regret at having to completely blame Jagger for everything about what happened at Altamont. There was a lack of nuance from the magazine when discussing the tragedy, take that in what Wenner said in the magazine’s 1,000th issue: “We are going to cover this story from top to bottom. And we are going to lay blame.”, while then turning around and saying that their conclusion never made anyone content. There was never a moment where Jagger had to become the only enemy, but he was the easiest person to attack for a moment in time. This is something still prevalent in today’s culture too, something that is almost a direct effect of this exact event. There always has to be a villain, there has to be an inhuman evil from exactly one person or group that all blame is to be directly attributed too. There are no further thoughts, there is nothing to discuss once blame has been rested - there is nothing to be learned from tragedy. It’s the same anti-intellectual lull we still find ourselves in, maybe even more so now - the idea that there is nothing to be learned from only gawked at in the face of disparity. It comes from a place of, to Wenner’s exact word, privilege - how no one is allowed to be wrong or accept defeat, how a person could be stabbed to death at a concert that many people poorly planned but only one singular band member is blamed for everything, and how this mistake will find itself consistently repeated.

What was your reaction to the magazine (Rolling Stone)'s coverage of the tragedy at your concert in Altamont in 1969?

I didn't think it was really justified, to be perfectly honest. It was pretty unpleasant. Perhaps there was a feeling in the San Francisco community that that sort of thing shouldn't happen there. Don't forget, Rolling Stone was thinking of itself very much as a San Francisco magazine. At the time it was such a traumatic event for their community. Of course, we had to shoulder our share of the blame. Which we did. But we weren't the only people that were responsible. - Mick Jagger to Gerri Hirshey, 2007

Altamont didn’t end after the band exited the stage. It became a circus of finding the reasoning for something so disturbingly devoid to humanity it could almost fit as a lyric in Sympathy for the Devil. Jagger, suddenly the image of all that was wrong with his generation, remained the most levelheaded and mature person during the whole issue. He understood the reaction even if he knew it was objectively a morally bankrupt and intellectually void one. He handled what had to be handled because if he hadn’t things may have somehow been worse, even if that seems like an impossible feat. Jagger was crucified by the culture for his handling of Altamont, though it bled more into a plea of what could he do? If he had stopped the show he’d have started a mob, more anger and violence erupting from his choice, had he chosen to ignore the situation and burn the tapes of film capturing the crime he would’ve been seen as trying to conceal the truth. He was at a loss of what any public figure could do, being treated as the crux of everything people hated about his generation. It was never about the murder, it was never about proper blame, it was about finding a figure to pin blame upon for the way the world was. Jagger protesting with the people, writing anthems of the time against the war, and being as peaceful as someone who had the heat of the world on his back could be, yes that was him but he was also the face of counterculture, the one unafraid to speak for himself and usher in the idea of freedom and individualism that others were afraid of embracing so openly. When something bad happened under the eyes of who had become cocky about himself, it was easy to want to nail him upon the cross he was boasting about never touching. In recent decades, the public has softened to Jagger and he’s hardened towards them, no longer the sole receiver of blame as much as the be-all, end-all of what it means to live on no one’s terms.

Death at concerts has only become more rampant in recent years. But no one is blamed for the would’ve and should haves like Mick Jagger was. It becomes more about the worry of how this affected the artist, how they couldn’t stop the show in fear of disappointment as opposed to the person who had died. Take the Astroworld tragedy as a sign of this, Travis Scott saying he couldn’t see the problems while in 1969 Jagger could see far enough to shut down any issue that arose. When a concert goer at a Taylor Swift concert had to be carried away and pronounced dead shortly after the show started, it still went on. There was no cancellation for the tragedy, yet Jagger was upheld as an antichrist for not ending his show. In 1970, with the release of Gimme Shelter and the acknowledgement of the blame he had for the tragedy, Mick Jagger essentially wrote the blueprint for how one should act in a situation such as this one. Under the circumstance at being held at gunpoint and knowing his fear in the situation would not only endanger thousands, knowing that being the most famous face in rock gave him the ability to de-escalate where he could, to not only take complete blame in the public eye for the incident and work to make sure something like that didn’t happen again, understanding that his negligence lead to four deaths and working for the next sixty years to run a show so efficient there hasn’t been a tragedy in the vein of Altamont under his watch since. Jagger had no protection from anyone while making these decisions, no sympathy for what had happened came toward him. There is little to no reason no other artist shouldn’t have followed in his steps. He had everything completely understood in a time when this was unprecedented, his aim for responsibility and growth, for acknowledgement.

In December of 1971, Don McLean would release his single American Pie from the album of the same name, an eight-minute magnum opus that detailed the last decade of culture in the United States, specifically in the effect music had on the world at large. The last verse was dedicated to Altamont, McLean christening it the day the music died. That title was originally attributed to the day Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens were killed in a plane crash, but was recontextualized to showcase the end of the most turbulent decade in American culture in recent history. The thing was, the music didn’t die, neither did the hippie generation, nor the peace movement. They were killed at a Stones concert on a cold December night. It wasn’t that they had to die. They could’ve been saved. But no one learned, and much more died than had to fifty-five years ago.

Praising Mick must have been difficult, but I'm glad you did. Even though it seems painfully obvious to our generation what a foretold tragedy Altamont could be, I don't think it was that obvious to them. Even people who were closely associated with Mick — like Marianne Faithfull — blamed him (and Keith) for what happened in Altamont and never quite acknowledged that it could have been much worse. Keith, in his naivety, even threatened to leave the stage, while Mick, in a resilience that would be repeated years later when a uninvited fan came on stage, continued determined to sing.